Basic Process Mapping Concepts

What is a Process?

A process is a series of actions or steps taken in order to achieve a particular end. A process is a transformation; it transforms inputs into outputs. For example, a process is the mechanism by which raw materials are converted into products.

Formally, the ISO Definition of a process is given in ISO 9000:2000 clause 3.4.1 as "a set of interrelated or interacting activities that transforms inputs into outputs". Inputs to a process are generally outputs of other processes.

This definition is at the heart of the Triaster Suite, and the essence of process mapping is to recognise that organisations that perform this transformation well generally manage to meet or exceed customer expectation and those that do it best are invariably the most successful.

What is a Triaster Process Map?

A Triaster process map is one of many tools for describing the way things are done. It can be thought of as a ‘User Guide’ to your organisation; it is the manual that shows how your organisation operates and provides employees the information to perform it.

Triaster process maps are produced using the Noun-Verb Method. This is a powerful, yet very simple way to document a business process. It has been thoroughly proven in hundreds of organisations to deliver process diagrams that are useful to a widespread, non-specialist workforce, and at the same time to business analysts. The Noun-Verb Method perfectly balances the need for simple, comprehensible process diagrams with sufficient detail to enable the identification and analysis of performance improvement opportunities.

To understand the Noun-Verb Method, it is helpful to consider the definition of a business process. The essence of a business process is that it transforms one thing to another. A Customer Order is transformed into a Delivered Product. A Supplier Invoice is transformed into a Supplier Payment. A Staff Vacancy is transformed into a New Employee. A process then is defined as:

a set of interrelated or interacting activities which transforms inputs into outputs

The Noun-Verb Method simply adopts this definition of a process, and applies it rigorously.

A process map drawn using the Noun-Verb method is a diagram that clearly identifies the main steps involved in performing the transformation and the items used and produced when the process is complete.

In Process Navigator, the term Activity is used to describe something you do, and the term Deliverable is used to describe something you produce. Activities are the steps of the process and are described using verbs; Deliverables are the items produced (or ‘delivered’) when each step of the process is complete and are described using nouns.

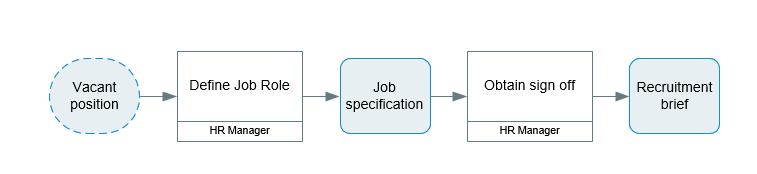

In Process Navigator, there are four other words with special meaning. These are: Inputs, Outputs, Suppliers and Customers. To help explain these terms, the diagram below shows part of a map of a recruitment process. In this diagram, the Activities are ‘Define job role’ and ‘Obtain sign off’. The other symbols are the Deliverables.

Outputs are the Deliverables produced by an Activity. These Outputs then become Inputs to other Activities; for example ‘Job specification’ is both an Output from ‘Define job role’ and an Input to ‘Obtain sign off’.

Suppliers are the people, organisations or Activities that produce the Inputs. Customers are the people, organisations or Activities that use the Outputs; for example, for ‘Job specification’, ‘Define job role’ is the Supplier and ‘Obtain sign off’ is the Customer.

The rules of the Noun-Verb method are very simple:

- Each Input or Output is described using a noun; each Activity is described using a verb.

- Each separate page of a process map must have at least one Page Input (i.e. a Deliverable with no Suppliers on the same page) and at least one Page Output (i.e. a Deliverable with no Customers on the page).

- A recommendation rather than a rule is that in the process map itself, no two verbs can be directly connected, and no two nouns can be directly connected. This recommendation can be strongly or weakly enforced depending on the nature of the content being produced and the level of detail.

This basic discipline of always specifying at least one Output (Noun) after every Activity (Verb) turns out to have highly beneficial knock-on effects throughout the model.

The first major benefit relates to the difference between Activity and Productivity. In the Noun-Verb Method, the verbs represent 'work performed'. The problem however is that a person can perform work all day long and not actually deliver anything of any value. The nouns represent 'product delivered', i.e. they explicitly identify the benefit of performing work. So, in the example map referenced above, the first verb "Define Job Role" is in and of itself not at all valuable, in fact, it represents a cost to the organisation. The value of performing the work however is explicitly documented in the output that is delivered, in this case the "Job Specification". In the Noun-Verb Method, the process author is required to document Activity and Productivity. As such, they are required to understand precisely why a given Activity does actually deliver something of value, and to record precisely what this is. Without the discipline of Noun-Verb, the tendency is to focus very heavily on the verbs, and the process map then simply becomes a list of things people do; it is what people deliver that matters most however, and the adoption of Noun-Verb requires equal focus on delivery.

A second major benefit of explicitly separating out nouns and verbs is that Investment and Return-on-Investment can be modelled. Clearly, the verbs in the process model represent areas of investment; a person has to be paid to perform a task, or machinery purchased and so on. The nouns on the other hand represent the return for making that investment. So, "Define Job Role" might cost £700, and in return for this investment, a "Job Specification" is received. Using the Noun-Verb Method it is possible to perform this analysis on a micro or macro level simply by aggregating costs.

A third major benefit comes from the recognition that the verbs in the model typically relate to the work people perform; as such, attributes relating to Responsibility, Accountability, Time, Effort etc. are typically stored in the model behind the verbs. The nouns however typically relate to the information sources in the organisation. One is therefore more interested in understanding the applications used to produce or store the output, the location of the template to produce it, etc. By separating the nouns from the verbs, the handling of metrics that describe the model is made much clearer, more tractable and more useful.

What are Process Interfaces?

A ‘Process Interface’ is the point at which work passes from one organisational unit to another. When documenting a business process, the four interfaces described below are generally the interfaces that are of most interest:

Worker Interface

This is the point at which a person completes a task and hands it to the next person in the process in order for them to continue production. Worker interfaces are generally obvious in physical production systems such as production lines. In business or administrative processes, Worker interfaces tend to correspond to in-trays and out-trays, e-mails, work instructions and letters. Worker interfaces are of keen interest to business analysts because much of the latent delay in completing tasks can be found in the interval between one worker finishing a task and the next worker beginning theirs.

Departmental Interface

A Departmental interface is a particular kind of worker interface. It is the point where an interface relates to two people from different departments. Departmental interfaces are also of specific interest to business analysts. Departmental interfaces often suffer from the worst side effects of organisational structure and hierarchy. In addition to the latent delay in handing over work from one person to the next, Departmental interfaces are characterised by conflicting priorities, management politics and an ‘us versus them’ mentality. It is striking how the human tendency to associate closely with colleagues of the same skills and background actually overrides the organisational requirement to produce saleable goods or services better than its competitors.

Customer Interface

The Customer interface is perhaps the most important interface. This is the point at which goods or services are moved from the ownership of the organisation into the ownership of the customer. The Customer interface is generally characterised by point of sale and delivery operations such as couriers, tills in shops, shopping channels and websites. The Customer interface is vital to an organisation’s future success but surprisingly, in many organisations, little work is done to understand it. Organisational change really should begin by getting the Customer interface right and moving from there back through the organisation so that the upstream processes support the customers’ requirements.

Supplier Interface

The modern corporate environment is not just one of companies competing with each other, but one of whole supply chains competing against whole supply chains. A company is only as strong as its weakest supplier. It is therefore important to establish the interface at which goods move from the ownership of the supplier to the ownership of the organisation. In addition, this interface should attain the level of quality and efficiency required by the Customer interface of the organisation that ultimately sells to the final consumer.

The modern perception of organisational interfaces is to view all worker interfaces as Customer/Supplier interfaces. Some of these will be internal customers; indeed any person that uses the outputs of another should be treated as that person’s customer. In most cases, it is not necessary to distinguish between internal and external customers as they both carry the same level of importance in the modern workplace.

It is also generally true to say that modern organisations actively seek to weaken the negative side effects of the departmental interfaces by strengthening the corresponding Customer interfaces. Cross-functional teams are drawn together from either side of the departmental interface in order to smooth the path of work passing through departmental boundaries. Individuals are encouraged to consider the needs of their customer before the operational requirements of their manager: a radical departure from traditional management.

Defining Interfaces with Process Navigator

Process Navigator enables individuals in an organisation to document the worker interfaces of which they are a part.

The Outputs an individual produces constitute their Customer interfaces. The Inputs an individual uses constitute their Supplier interfaces.

Process Navigator opens up communication channels and helps establish Customer/Supplier interfaces. This often means that the workforce will independently modify its working practices in order to improve the quality, timeliness and cost efficiency of the Deliverables it produces for its customers.

Process Navigator helps the business analyst understand the totality of a business process, as defined by its interfaces, without clouding the picture with unnecessary detail. It also enables the detail to be accessed when needed. Process Navigator is a tool for hiding organisational complexity but, when necessary, for also revealing detailed operational working processes.

Why use Process Maps?

Process maps are a powerful tool for understanding and communicating the jobs you carry out during a normal working day, and because they are diagrams, they are easier and more pleasant to read than alternatives such as procedure manuals.

Process maps are used more and more to help an organisation capture a snapshot of its day-to-day working processes. Knowing how a company works today makes it possible to improve the way it works tomorrow, in a controlled, measurable, thoughtful way.

Understanding the steps taken to convert Inputs to Outputs enables better processes to be designed and affords a way in which workers can contribute to improving their own productivity and job satisfaction.